Foreword: When we began writing this post, Saule Omorova’s appointment for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and her academic credentials were being dragged through the media. The process famously did not go her way but we are nonetheless grateful for it as it gave us the opportunity to become acquainted with some of her work. So although we're hopelessly late for the party, perhaps this post will contribute to keeping the discussion alive in a more fruitful, i.e. non media-frenetic, manner.

In our previous writing, we have focussed solely on constructing and explaining the Accounting View (AV) of ‘money’. Our claim being, that what is usually considered a ‘special good’, i.e. fiat money, must actually be seen as multilateral credit. So, according to the AV, all things financial, including notes and coins, are actually just types of credit. Money, as it is generally defined, does not exist.

All modern schools of thought of course accept that credit exists and that it forms a large part, if not virtually the whole of the banking system[1]. The difference to the AV is that, because we claim that money does not exist, credit can not be seen in relation to it. Within the AV, credit is not the act of borrowing money! Credit is the act of receiving goods without giving goods of equal value -- a fact which is recorded by an accountant (banker). As we shall argue below, this definition is not only useful for thinking about credit in the abstract or for describing babysitting cooperatives but can be used for studying our actual financial system, including arrangements among firms, banks, governments and even countries as a whole.

The standard view (h/t JP Koning) treats fiat money as a ‘bubble asset’ whereby the government, by means of some inherent power, say the power to levy taxes, confers a positive exchange value to otherwise worthless bits of paper. Bank money is subsequently a promise to pay fiat money. Others invoke an historical evolution from commodity money to fiat money to make the case that fiat money is itself a form of credit to which other credit instruments can be put in relation. Here are some examples of how these relations are conceptualised (emphasis ours).

(...) think about a monetary system under a gold standard, and think not about money and credit in the abstract but rather about concrete financial instruments: gold, currency, bank deposits, and securities.

In such a world gold is the ultimate money because it is the ultimate international means of payment, and national currencies are a form of credit in the sense that they are promises to pay gold. National currencies may be “backed” by gold, in the sense that the issuer of currency holds some gold as reserve, but that doesn‟t mean that these currencies represent gold or are at the same hierarchical level as gold. They are still promises to pay, just more credible promises because the presence of reserves makes it more likely that the issuer can fulfill his promise. Farther down the hierarchy, bank deposits are promises to pay currency on demand, so they are twice removed promises to pay the ultimate money, and securities are promises to pay currency (or deposits) over some time horizon in the future, so they are even more attenuated promises to pay. Here again, the credibility of the promise is an issue, and here again reserves of instruments that lie higher up in the hierarchy may serve to enhance credibility. Just so, banks hold currency as reserve, but that doesn‟t mean that bank deposits represent currency or are at the same hierarchical level as currency.

The currently existing U.S. financial system is in essence a public-private franchise arrangement for the distribution of a unique collective good: the monetized full faith and credit of the United States. At its core, it is a system for supplying and dispensing a uniform national currency and its credit equivalent, dollar-denominated debt. The sovereign public, acting through its central bank and fiscal authorities, is the ultimate creator, or issuer, of this critical collective good. Privately-owned banks and other financial institutions, in turn, distribute sovereign credit-money throughout the economy, effectively collecting “privatized seignorage” for their services.

Without going into the details, some features stand out when we apply the AV.

Mehrling constructs his hierarchy beginning with gold as the ultimate money. Forms of national credit instruments are then placed into a hierarchy below gold as promises to pay or redeem that which comes above. By doing so, he has designed a way of upholding the scarcity principle, without having to claim that fiat money is itself an inherently scarce resource.

At every level of the system, the availability of money from the level above serves as a disciplinary constraint that prevents expansion; credit is payable in money, but money is scarce.

So, while gold may no longer play a role in modern banking systems, the ability of currency issuers to constrain the amount of their particular type of credit has the same effect as gold for any credit instrument that happens to reside further down in the pyramid.

Omorova presents a similar hierarchy but without mentioning gold or any other tangible good. Instead, she claims that fiat money is a special, collective good which has positive value due to the creditworthiness of the nation. That good is then lent out to commercial banks.

J.P. Koning does not present a hierarchy as such (although he does mention ‘inferior’ credit instruments), nor does he refer to ‘money’ as a special good. But his classification tree also relies on the concept of ‘redeemability’ of one type of credit instrument for another.

What these examples have in common is that all types of money and credit, however defined, can be seen as scarce resources in Lionel Robbins’ sense[2] and thus can be modelled as commodities from the point of view of the user.

A logical consequence of adopting the AV, on the other hand, is that records can not be considered commodities in the same way that gold or other goods can. They are not things of which there is any meaningful supply. They are records of things having changed hands / ownership or of services having been performed. As such, they must be conceptually separated from what is being recorded which we have characterised as transactions of ‘goods for nothing’. Every transaction leads to an update of the records of both parties involved. Depending on the buyer’s and seller’s respective trade histories, this can result in balances on either account being negative, positive or zero. So while Mehrling can state that gold is the ultimate money, the AV forces us to make a decision. Gold can either be that which is traded -- i.e. bullion -- or it is a metallic recordkeeping device -- i.e. a credit token -- in which case it is not part of the transaction[3]. But it cannot be considered both at the same time. (For a more detailed discussion of tokens and why they must be understood as part of an accounting framework and not as commodities, we can again refer you to our paper in which we laid out the basics of the AV).

For the same reasons, it makes no sense to think of credits or debits being borrowed or lent (this leads to the circular argument that credit is the act of borrowing credit…) or being transferred from one account to another. Accounts are simply credited and debited.

Nevertheless, such records are of value to us because they provide us with proof of our trading history. When we become indebted through receiving more goods than we give, we are officially given credit for our promise to return goods of equal value in the future. As participants of the system, we trust that such promises will be kept and goods will thus be forthcoming. This gives meaning and value to the corresponding credits.[4]

Disaggregating the Accounting View

Up until this point, we have not only restricted ourselves to explaining the phenomenon of ‘money’ from the AV. Using Wicksell’s concept of One Bank, we have also abstracted away from institutions that make up the banking system itself. So, to explain the relation between institutions within and ultimately beyond our modern banking system we must now proceed by disaggregating the AV.

Using the above definition of credit and some simple accounting arithmetic, we will attempt to describe the basic institutions and operations of our current financial system from the Accounting View, illustrating them with some simple examples along the way. The main characters in these examples are A and B, who are best seen as individuals and the government that acts on behalf of the public. These entities engage in goods transactions with one another. On the recordkeeping side, we have commercial banks Alpha and Beta, a central bank, a primary dealer and non-bank financial institutions. Both our subjects as well as our financial institutions can have accounts at (other) financial institutions which are debited and credited.

Credit Analysis

J. P. Koning writes:

Dollars issued by banks are secured by the banks' portfolio of loans [...].

As for central banks like the Fed, they are just special types of banks [...] and so the dollars they issue are also subject to credit analysis.

In other words, the perception of the soundness of the loans kept on each institution’s books will determine to which extent the corresponding credits are, well, credible. This is straightforward, at least on paper, when each institution is treated separately, as done by Koning above. Central banks are special in that the types of debts and the class of debtors, i.e. mainly public debt / the public, are different from what is typically represented on the left hand side of a commercial bank’s balance sheet. Again, the debts we refer to here are promises by bank debtors to deliver goods in the future and not promises by the bank to pay currency on demand. And so it must be the former to which credit analysis applies and not the latter. Consequently, the classifications presented in the three quotes above must have a different meaning in the AV. But to gauge their significance, we must first untangle some more building blocks.

‘Transfers’

The AV says that money does not exist and credits aren’t things that reside on or can be transferred from one account to another. So what does it mean when we ‘transfer’ ‘money’ / ‘deposits’ from one bank to another?

Let’s begin with our first example:

A receives goods worth $100 from B, both of whom have a balance of $0 in their respective bank accounts to begin with[5]. A is banked at Alpha Bank, B at Beta Bank. Each bank has an account with the other bank. So A’s account is debited with $100 and B’s is credited by the same amount. But since each bank’s balance sheet must balance, there must be an offsetting entry for the ‘transfer’ on either bank’s ledger.After the transaction:

Table 2

As we can see, the act of purchasing goods involving two banks means that those banks have now entered into a relationship with one another. This is in contrast to the term ‘transfer’ which implies an object moving from one bank to the other but no such relationship. In order to rate B’s credits at Beta Bank, we have to look at A’s debt which is recorded at Alpha Bank. This changes slightly if we insert a central bank in between Alpha and Beta.

After the transaction -- now, with a central bank:

The central bank, in its function here as a clearing house / banks’ bank, becomes a conduit for the credits and debits of its two member banks. But B’s credits at Beta Bank can still only be as good as A’s promise to deliver goods in the future[7].

We can also add a further feature to this central bank, namely that of the public’s bank. The government, acting on behalf of the public, can now purchase $100 worth of goods from A which pays off A’s debt to society[8]. The government, on the other hand, has incurred $100 in public debt.

The result is completely analogous to table 2, with the central bank and the public taking the place of Alpha Bank and A respectively.

‘Deposits’ and the Unit of Account

In order to proceed we need a more precise definition of a ‘deposit’. Taking the transaction leading to Table 2 as a normative statement, we can say that ‘deposits’ are credits that must live up to a certain standard. Namely that of making sure that B will receive something worth roughly as much as the goods he gave to A. B wants to be covered against losses potentially caused by debtors, as measured in the unit of account at the time of the original transaction. One could say that a ‘deposit’ is actually a loss-protected credit. The question is, how can such credits be kept safe from the risk associated with debt? The AV suggests the following three safety realms.

1. Individual: Due Diligence, Credit Appraisal & Interest

First off, it makes sense to ensure that debtors cause as few losses as possible. Their creditworthiness and the feasibility of the investment being financed must be assessed, collateral can be posted and a fee, say an interest rate, can be levied to cover expected, average losses.

2. Intra Bank: Bank Equity & Reserves

As a second line of defence, banks can establish a communal buffer. Creditors can pledge some of their credits that are marked down if unexpectedly large losses occur. Naturally, these special creditors will expect to be rewarded when business runs at a profit. In addition, management can put aside assets, such as gold, which are then sold or withhold profits from creditors which are then written off.

Should both lines fail, losses can be shared by a larger class of creditors. As Table 2 shows, this might be creditors of other banks through lines of credit among banks. Seeing as commercial banks are run to make a profit, such loss communalization is unlikely to carry on for long. Existing lines of credit will be terminated and / or lending rates raised, adding to the original stress. So, to the extent that Beta Bank is not left to its own devices, at which point its ‘deposits’ might fall short of their normative goal, the government can agree to risk-pooling by pledging public credits or assets. It can take on the risk associated with the imperilled bank’s ‘depositors’ only (deposit insurance) or with all of its creditors (LoLR).

What is important to see is that any web of credits and debits, no matter how long and complex, can always be traced back to the debtors who received more goods than they gave and creditors who gave more than they received. Any other arrangements are about managing the risk associated with such basic credit. That also means that no amount of complexity can make that fundamental risk disappear completely. It can only, knowingly or unknowingly, be offloaded onto others.

Redemption vs. Contractual Obligations

As we have stressed in our previous writing, the terms redemption or payment have a very specific meaning in the AV. They only refer to reciprocated goods trades, not to the records of trades. You are redeemed or paid once you receive an equal amount of goods you gave up before. Ultimately, redemption or payment finality is achieved when the net balance on one's account(s) sums to zero.

Nevertheless, it is of course perfectly common to specify that one type of account can be transformed into another, either at the same institution or a different one, following some trigger event. One such event goes by the name of ‘withdrawing'. Hereby, as a bank creditor, I can make use of my contractual right to change my institutional affiliation from my bank to the central bank at a predetermined rate of approximately 1:1 on demand. Since central bank notes are not digital, the bank must keep notes on reserve to meet that obligation. Other than the distinct tangibility of cash and coins, this right is not much different from my right to change my affiliation from the central bank to a commercial bank (‘depositing’) or from one commercial bank to another (‘transferring’) or any other ‘financial transaction’ at a predetermined rate. The fact that ‘withdrawing’ is stressed to the extent that it is said to define the essence of bank money (see: bank deposits are promises to pay currency on demand) probably tells us more about the way in which some theories are constructed than it does about the the importance of this specific contractual obligation in comparison to others. If a theory implicitly equates the unit of account with central bank (or treasury) credits, then such a hierarchy of obligations is perhaps a logical conclusion. But the AV gives us no reason to just assume that equality.

Open Market Operations

The astute reader may wonder how the AV accounts for the actual operations surrounding the so-called ‘monetization’ of government debt (as opposed to the simplified presentation in Table 4). The first question is, why do central banks not just take on government debt directly? In line with standard theory, we suggest that publicly floating debt is an attempt at solving a principal / agent problem. If central banks treated government debt in the same way banks treat your or my debt, we would be faced with a bank that is owned by the government, has its managers appointed by the government but also benefits the government by extending credit to it. Hence, the introduction of an intermediate step by which loan appraisal and pricing are forked out to the public through an independent bank (primary dealer) -- a step that is later reversed when the central bank performs its open market operations.

Step 1: Bonds are floated and public goods purchased

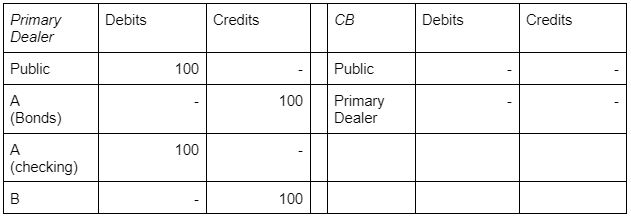

Successful bidder A prices the bond, assumes the risk associated with it and has his checking account debited accordingly. The public’s debt is recorded at the primary dealer and B is credited for selling goods worth $100 to the public (which is the reason the government incurs debt in the first place).

Table 5

Step 2: Open Market Operation

The central bank now takes on the public as a debtor, neutralising A’s entries, while crediting the primary dealer’s reserve account.

If we leave out the accounts that now net to zero, we are left with the following picture:

The end result is identical to Table 4, which in turn is analogous to Table 2. In other words, if we look past the special procedures surrounding government spending, public debt and central bank credits are no different from any other debits and credits. We can only construct a difference through theories that assume a priori that account entries incurred by the public, or recorded at a public bank, differ fundamentally (see: a unique collective good) from credits and debits incurred by individuals and firms. A stringent look at the accounting shows us that this theoretical distinction is uncalled for.

Summary

The above foray shows that the banking system can be characterised as a set of norms regarding credits commonly known as ‘deposits’. As such, it can be theoretically delineated from the rest of finance that does not offer such safe accounts. Whether this theoretical distinction is meaningful ultimately depends on the types of obligations that exist between banks and non-banks.

Looking again at ‘deposit’ accounts in isolation, it is a stretch to claim that the central bank has a natural monopoly on them or that central bank ‘deposits’ define what ‘money’ is. Perhaps credit analysis will show that in many cases the public is indeed a more worthy debtor than a collection of individuals and firms. But that is by no means a logical necessity, nor an historical fact. It is probably safer to say that whichever institution is most trusted to fulfil the normative goal of ‘deposits’, is likely to set the standard that others will try to follow. On the other hand, in light of the discussed interconnection, it is questionable whether one institution’s risk can actually be cleanly delineated from another’s. Consequently, it might be better to think of all ‘deposits’, including accompanying debits, as the accounting entries that make up a currency.

What can be said with certainty is that no system that relies on credit to facilitate trade is failsafe or non-defaultable. Any credit system is only as good as the sum of its participants.

Looking at the risks involved, our choice of having a banking system that consists of publicly and privately owned entities presents us with a management problem. If, as we have argued, the service that all banks provide (recordkeeping) is a public good, then the design of the safety features detailed above must logically be uniform across all institutions and be designed and implemented with the public interest in mind. Only then can the public take on the residual risk from bank debtors so that the credits of all member banks remain true to the unit of account and thus form a uniform currency. It is this promise to socialise residual losses that is uniquely collective in nature, i.e. a unique collective good, not central bank credits or debits themselves. In fact, such a public guarantee could easily be administered without a central bank. Governments could simply have accounts at commercial banks, as was the case historically.

CBDC

Saule Omorova’s paper is actually not about money and credit but about implementing a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC). CBDCs are all the rage at the moment and hers is a plea in favour. In the following, we will attempt to translate Ms. Omorova’s proposal into the Accounting View to see whether this generates any new insights. Specifically, we will look at three types of account entries that a CBDC, as Omorova envisions it, will likely produce.

First off, there is the intended ‘migration’ of ‘deposits’ from banks’ balance sheets to the central bank. Starting with a blank slate, A again buys goods worth $100 from B. Since CBDC accounts do not allow overdrafts, A’s debt will be recorded on his account at Alpha Bank. This will prompt three more entries by which B’s credits and the Alpha Bank’s overdraft at the New Discount Window are recorded, leaving us with the following picture:

The provision that debts must be recorded on banks’ books whereas credits are recorded at the central bank, leads to a situation that is completely analogous to the bank ‘transfer’ described above in Table 2. As with any accounting event involving corporate entities, central bank credits do not just affect the liability side of its balance sheet. They always affect both sides of both balance sheets -- for every credit there must be a debit. Also in line with table 2, when the initial safety barriers at Alpha Bank fail, the New Discount Window becomes the direct conduit for losses to central bank creditors, equity holders being first in line to take a loss. And since central bank equity holders are the public, such losses effectively accrue to the same class of people as those who have CBDC accounts. In this sense, central bank credits are not non-defaultable, as Omorosa claims. It is just that debits are recorded on a communal account (equity) whereas credits are recorded on individual accounts (CBDC accounts). Debts are socialised, credits privatised. Another way of putting this is that, at least with zero interest, CBDC is functionally equivalent to unlimited deposit insurance under current arrangements.

If the central bank charges interest at the New Discount Window, this represents a gain for the public that can make up for potential losses. From the banks’ perspective, this is a cost which they will aim to minimise or even circumvent.

This leads us to the next case, which is that of alternatives to ‘deposit’ accounts that banks might offer, should the New Discount Window not be attractive for them. For this, it is useful to think back in history. In times before most people had bank accounts, credits mostly took the form of either coins or notes. So if banks were prohibited from issuing coins and notes, most of their customers would fall away. In other words, by tying prohibition to an accounting technology (coins, notes), banks could be kept from offering a specific type of account (‘deposits’) due to the lack of practical alternatives. With the advancement of banking technologies, it has become more difficult to enforce such a prohibition. Money Market Funds and Stablecoins are some examples of how accounts can offer the same type of stability customers expect from a ‘deposit’, without the explicit contractual commitment of the latter. It is hard to predict what kind of financial innovation banks would come up with to circumvent CBDC and whether regulators would manage to stay ahead in enforcing the public monopoly on ‘deposits’.

Last, we will look at ‘helicopter drops’. Omorosa writes:

[...] the Fed will credit all eligible Fed Accounts when it determines that it is necessary to expand the money supply in order to stimulate economic activity and ensure better utilization of the national economy’s productive capacity. [...] In contrast to conventional monetary expansion through crediting banks’ reserve accounts in exchange for bonds or other assets, helicopter drops do not symmetrically increase the asset side of the central bank’s balance sheet.

The implied imbalance on the central bank’s books defies accounting logic. Credits to one account must be accompanied by an increase in debts or decrease in credits (i.e. debits) to at least one other account. So, while it is true that ‘helicopter drops’ are not accompanied by debt purchases on the open market, the conclusion cannot be that there is now an asymmetry, but that we must look elsewhere. Again, it is central bank equity that performs this balancing task. ‘Helicopter drops’ decrease public credits / increase public debt 1:1. The confusion in terminology is presumably caused by the fact that such a debit does not go through the same vetting process as described above under Open Market Operations. Consequently, debt that is potentially incurred this way (negative central bank equity) is not subject to the same dynamics associated with bond markets and compounding interest. But even non-interest bearing, perpetual debt, is debt. ‘Helicopter drops’ are fiscal operations as they implicate the public through debits to its equity account at the central bank.

Overall, we find Omorova’s strategy of considering changes to the asset and liability sides of the central bank’s balance sheet separately hard to square with accounting. Apart from perhaps leading to some blind spots or even inconsistencies, this is also a matter of language consistency. It is questionable, for example, whether allowing CBDC accounts to have only positive balances while leaving the corresponding debits to banks deserves the name People’s Ledger as only one of the two entries happens on a public ledger. The public private partnership that is the banking system is not suspended if individuals are given CBDC accounts of the type Omorosa envisions. Only a system of publicly owned banks with little to no exposure to the privately owned banking sector could fulfil that requirement.

Oliver & Antti

[1] We use the term ‘banking system’ to describe the sum of the central bank and its member banks.

No comments:

Post a Comment